The idea of creating your own UHF RFID tag from scratch is a powerful lure for engineers and makers. When an off-the-shelf tag won’t fit your unique product or environment, the question arises: how do you make a UHF RFID antenna? It’s a project that starts with simple materials but quickly becomes a deep dive into radio frequency physics, where success is measured in millimeters and millibels. Here’s a look at the real process, complete with the inevitable stumbling blocks.

It Starts with a Substrate and a Conductor, But the Devil’s in the Details

The core components are straightforward. You need a dielectric substrate—the base material. For prototyping, this could be FR4 (standard PCB material), Rogers laminate for better performance, or even rigid cardboard for a crude test. You also need a conductor to form the antenna pattern: copper foil tape, thin sheet metal, or conductive ink.

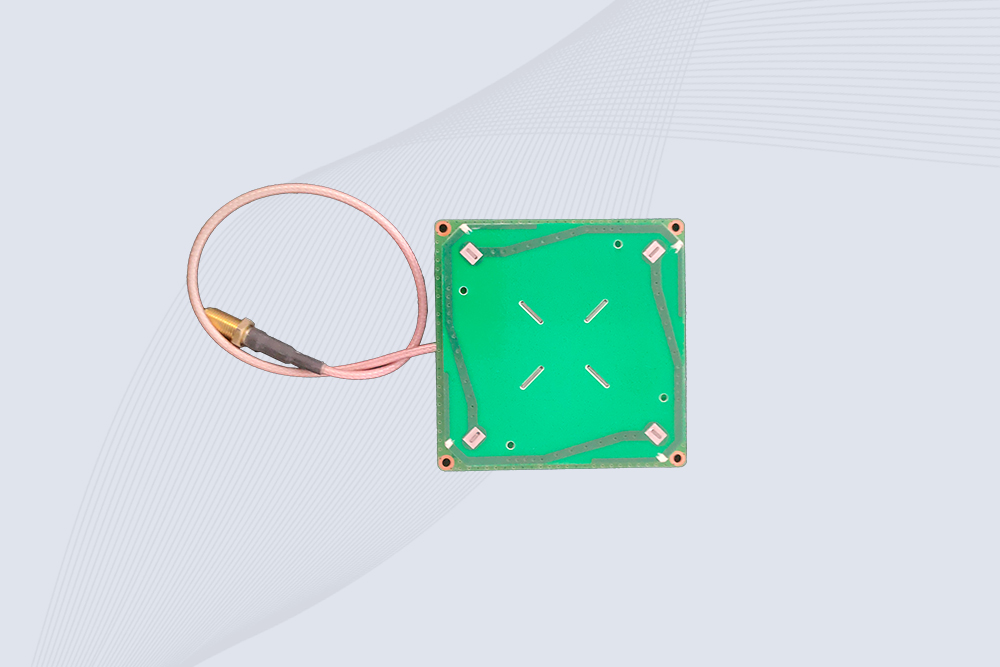

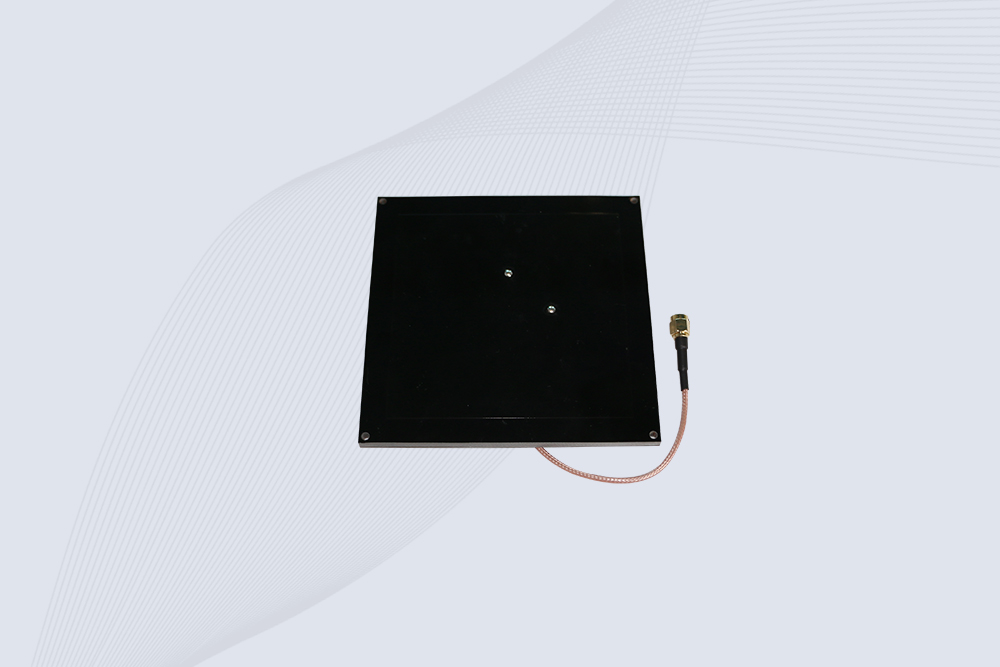

The first major choice is the antenna type. A dipole (two straight arms) is the simplest to model. A patch antenna (a square or rectangle) is more complex but can be easier to impedance match and offers directional gain. Most DIYers start with a dipole for its simplicity.

The Critical Phase: Design and the Math of Length

This is where you move from hobbyist to RF apprentice. The physical length of your antenna elements determines its resonant frequency. For a half-wave dipole at 915 MHz, the total length is roughly half the wavelength in your substrate material.

The formula is a guide: Length (in meters) ≈ (Speed of light / Frequency) / 2. For 915 MHz in air, that’s about 164mm. However, your substrate has a dielectric constant (Er) that slows the wave, meaning you need a slightly shorter length. If you use FR4 (Er ~4.3), your antenna will need to be physically shorter than 164mm. This is your first tuning variable.

The Make-or-Break Hurdle: Impedance Matching

You can cut a perfect 80mm dipole arm and still get a tag that reads only 2 inches away. Why? Because you’ve likely ignored impedance matching, the single greatest challenge in DIY RFID.

Your RFID chip doesn’t look like a 50-ohm resistor to the antenna. It presents a complex impedance, often something like 15 – j150 ohms (mostly capacitive). Your antenna must be designed to present the exact conjugate of this (15 + j150 ohms) at the feed point to transfer maximum power.

This is achieved through the antenna’s feed structure. A simple gap won’t work. You need to design a T-match or an inductive loop—small geometric features etched into the antenna arms right at the chip attachment point. These act as impedance transformers. Designing these without simulation software (like ANSYS HFSS or even free tools like Qucs) is pure guesswork. This is the step that separates a functional prototype from a failed experiment.

Fabrication, Assembly, and the Inevitable Re-Spin

Once designed, you fabricate: cut the substrate, apply the conductor, and etch or cut your pattern with precision. Then comes the delicate task of attaching the RFID chip strap. This requires a fine-tip soldering iron, conductive epoxy, and a very steady hand. Overheat the chip, and it’s dead.

Then you test. If you’re lucky enough to have access to a Vector Network Analyzer (VNA), you connect it and look at the S11 plot. You hope to see a deep, sharp dip at exactly 915 MHz. More likely, you’ll see a shallow, wide dip at 890 MHz. Your substrate’s Er was off, or your trace width was wrong. This is the prototyping loop: design, fabricate, test, tweak, repeat.

Why This Process Explains the Value of Commercial Tags

After a few cycles, you might get a working tag. But will it work consistently? Will it survive a drop, humidity, or being mounted on metal? Almost certainly not.

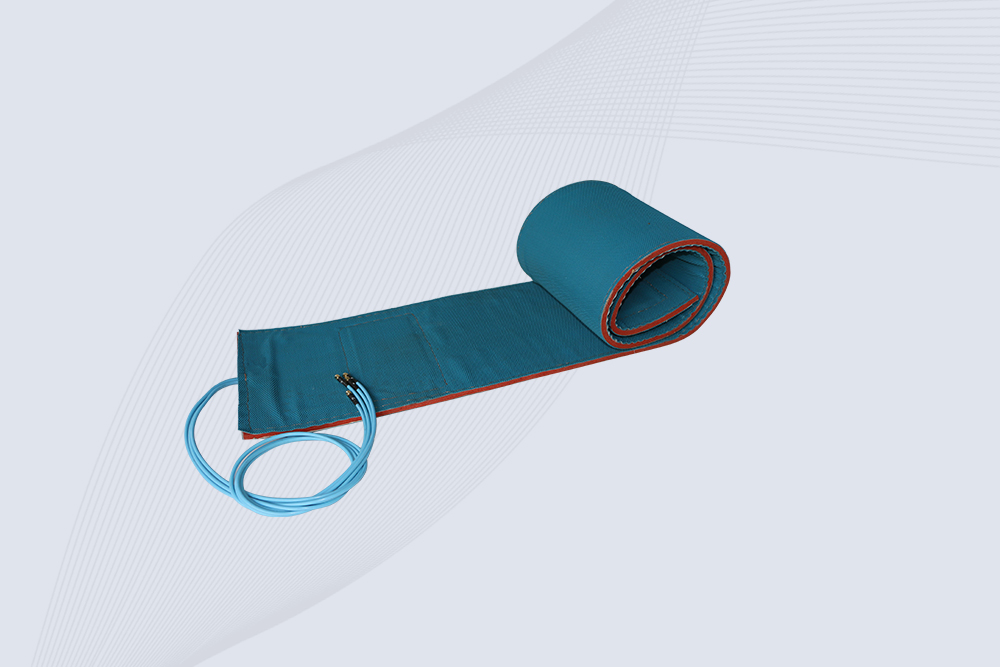

A commercially manufactured UHF inlay from a partner like CYKEO is the product of this entire process—but perfected and scaled. It uses precisely characterized materials, photolithographic etching, automated flip-chip bonding, and is tested on a sample from every production batch. The cost isn’t in the materials; it’s in the R&D, precision, and quality control that ensure every tag in a roll of 10,000 performs identically.

So, should you learn how to make a UHF RFID antenna? Absolutely, if you want an unparalleled education in applied RF engineering. It’s the best way to understand the constraints of tag design.

But for a product you’re bringing to market, an asset tracking system, or any application where reliability is non-negotiable, the most efficient path is to leverage that existing engineering. Work with a provider like CYKEO to select or co-design a tag that has already conquered these hurdles. Build one to learn; source professionally to deploy.

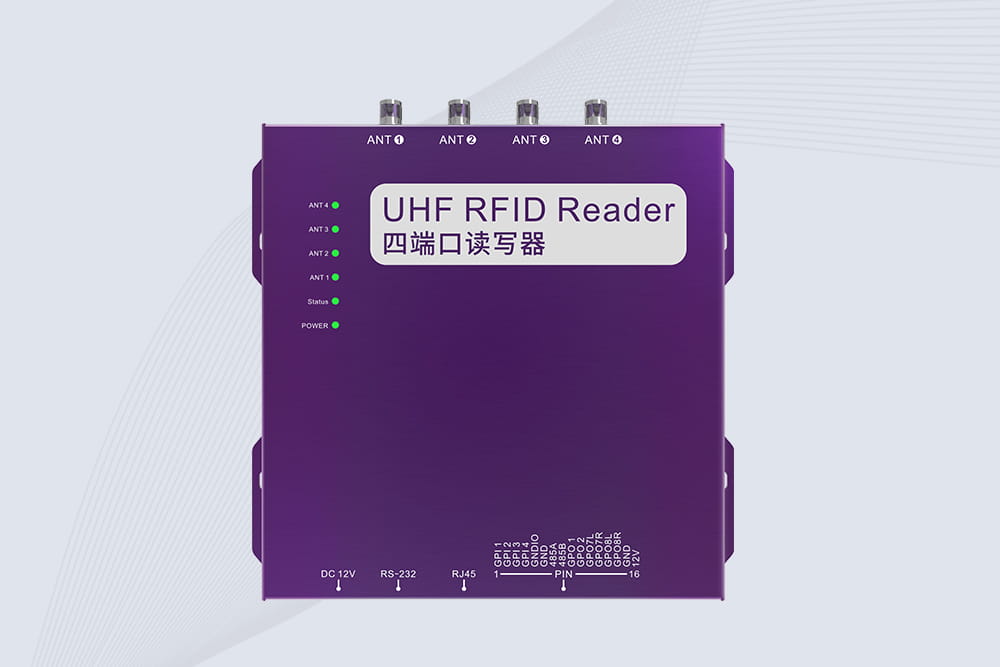

RFID Antennas Recommendation

Cykeo RFID IoT Solution Products R&D Manufacturer

Cykeo RFID IoT Solution Products R&D Manufacturer